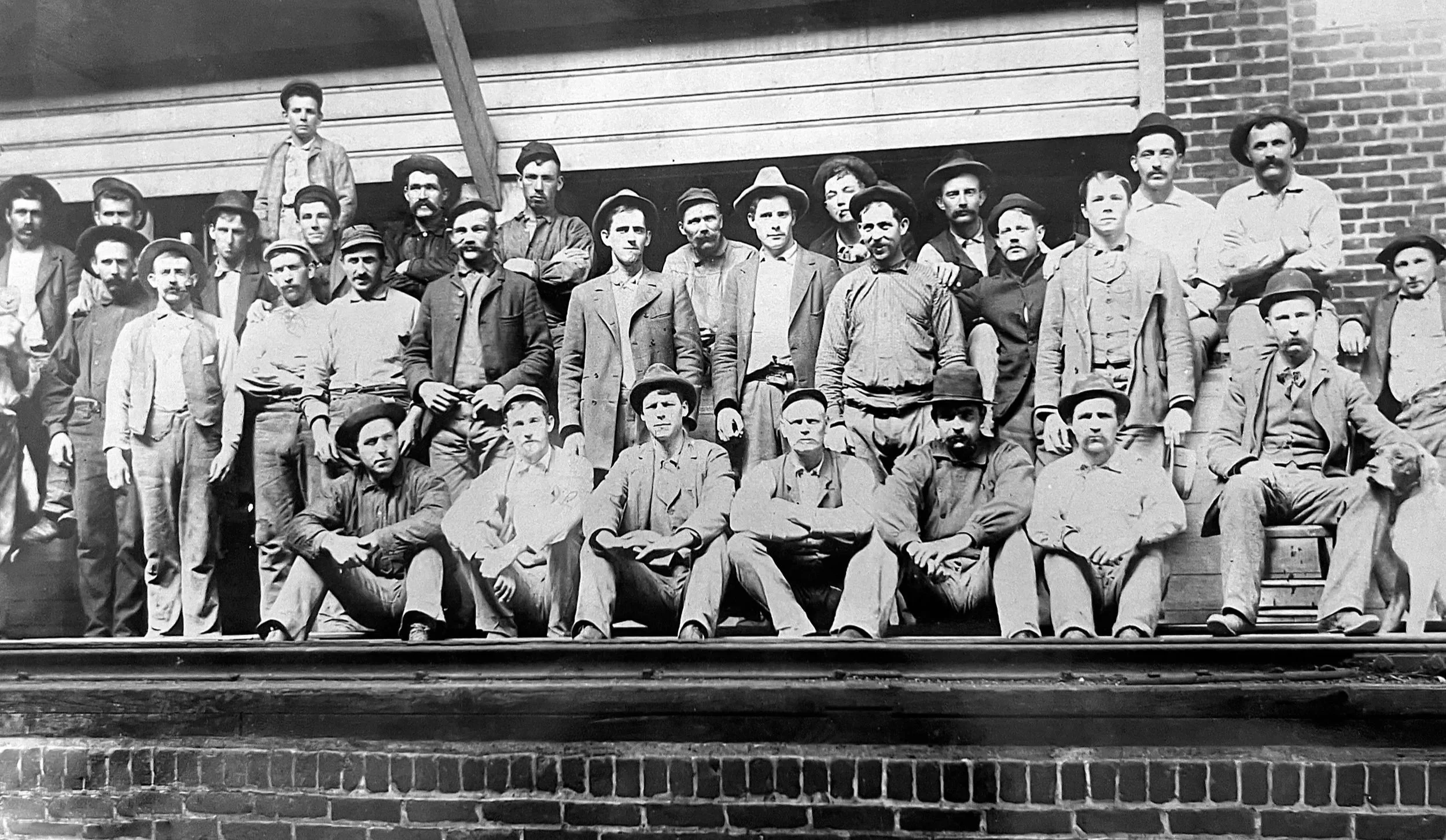

Unhoused workers walked the streets of Crockett looking for work along the Carquinez Straits

Unhoused workers walked the streets of Crockett looking for work along the Carquinez Straits